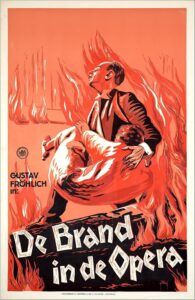

Opera Meets Film: The Birth Of A New Era In Carl Froelich’s ‘Fire At The Opera’

By John VandevertThe aftermath of World War One was defined in Europe, quite remarkably, by multiple, simultaneous cultural advances and experiments. These revolutionary developments ranged from classical music shedding its attachment to romantic tendencies and exploring expressionism, through art embracing the surrealist extensions of the mystical, to cinematic developments, and even architectural conflicts between modernism and classicism. In the Germanic world, suffering defeat in the Great War, despite its gravitas, did not stop innovation nor attempts to reinstate normalcy. One of those innovations-cum-normalcy restoring elements that emerged in Germany and entered the international scene can be considered “sound film,” which was a relatively new invention in these first two decades of the 20th century.

One of the German pioneers, Carl Froelich, helped establish the German variant of the “talkie,” or the sound film. From “The Night Belongs to Us” (1929), to many others, Froelich’s work was revolutionary. A particularly interesting film, “Fire At The Opera” (1930), is among the many films to use opera as the base of its plot and musical narrative. Shot at the Babelsberg Studios in Berlin, the film exemplified the continued domination of the sound film in the European world and marked the definitive emergence of a new era of film.

A Plot Fit For Opera

The film’s story follows the narrative of many famous love triangles, frustrated pursuits, and tried and true love-themed operas and operettas, from Johann Strauss II’s “Die Fledermaus” to Mozart’s “Cosi Fan Tutte.” Set in post-war Germany, among the wealthy upper class, General Director Otto van Lingen prides himself on his ability to capture the hearts of women. This time, however, he wishes to pursue choir singer Floriane Bach who is less enthralled with him than he with her. Bach works at the local opera house and in preparation for a production of Offenbach’s “The Tales of Hoffmann,” three girls are in the running for the female leads of Stella, Olympia, and Guilietta. This is a traditional staging of “Tales,” wherein one soprano is expected to sing all three women—today, usually, the roles are split between more than one.

Van Lingen jumps at this chance to get Bach’s attention by being her patron and ensuring she secures the role, but ultimately his efforts are undone by his secretary and friend Richard Faber, who aids Bach instead. Nevertheless, when they do meet, he tries to court her but this too fails. In light of this, Faber and Bach become close friends which angers van Lingen further, who assumes they are lovers not friends. Following an uncontrollable blaze at the opera house right before the evening’s production, van Lingen and Faber reconcile their disagreements. Upon seeing that Bach has fainted from the smoke, they both quickly rush to her aid. Van Lingen, realizing that the two really do love each other, refrains from interfering further and allows their romance to blossom.

A Vanguard Product of Its Time

Froelich’s film was praised by critics for its inventiveness and masterful ability to blend sound and dramaturgy: a relatively new feat, considering sound films had only been introduced to the world as a new medium for film in the late 1910s, and were not seen as commercially viable till the second half of the 1920s. In Germany’s case, three German inventors began working on the development of sound-in-film in 1919. Josef Engl, Hans Vogt, and Joseph Massolle perfected the “Tri-Ergon” system. “The Arsonist” (1922), as one of the first German films to use this technology, heralded the normalization of this system. By the end of the 1920s, it had become one of the dominant technologies in Europe, and the company behind it merged with its competitors to form what would become known as “Tobis Films.”

While modernist composer Paul Hindemith and those connected with the “Donaueschingen Festival” occupy a famous place in the history of this technology, it is the vast number of films using the technology that is, personally, most exciting. From opera films including the screening of Rossini’s “La gazza ladra,” to Max Mack’s “Ein Tag auf dem Bauernhof” (1928), and Tobis Films’ first project, “I Kiss Your Hand, Madame” (1929), by the start of the 1930s, sound films were all the rage. So advanced were sound films in Germany that even by 1929, some of the first feature-length talkies were being produced, including Walter Ruttmann’s “Melody of the World,” and Carmine Gallone’s “Land Without Women.” At the beginning of the 1930s, despite the American Great Depression and its global ramifications, sound films were continuing their process of cultural normalization. Following the creation of Wilhelm Thiele’s “The Three from the Filling Station” (1930) and Josef von Sternberg’s classic, “The Blue Angel,” (1930) the Berlin Chamber of Commerce and Industry declared, “By now, sound film has become firmly established.” Interestingly, the first German-language sound film to be released to American markets, “It’s You I Have Loved” (1929), took much from its American counterpart, “The Jazz Singer” (1927), which had been screened in Europe for the first time in London in the fall of 1928 and in Berlin without sound.

Froelich’s film was consequently swirling within a milieu of fast-paced advances both within and without Germany. 1930 also marked the emergence of the “talkie generation” in other countries including France, Poland, and China. Meanwhile, experimental approaches to the new medium were already underway, two of the most idiosyncratic being the French film “L’Age d’Or” (1930), and the Swiss film “Borderline” (1930). Froelich’s film is indeed tame and even conventional for a time aesthetically marked by the birth of post-war surrealism, with Salvadore Dali, American Art Deco, early modernism in music and its school-based derivatives, along with increasingly dramatic, aggressive, violent, humorous, and risque themes onscreen in films like “The Public Enemy” (1931). But, maybe, conventionality was something the viewing public sought? The larger sociopolitical climate of post-war Germany was hardly amicable. Following their defeat and the disintegration of the empire in 1918, and the costly punishments in the form of reparations inflicted by the “Paris Peace Conference,” Germans wanted to laugh. With Froelich’s film, they could.

Wagner & Offenbach Combine

In the film, one can find a quasi-production of Wagner’s 1845 opera, “Tannhäuser,” specifically the Act Two song contest “Sängerkrieg” when the guests are presented to Princess Elisabeth and Hermann, Landgrave of Thuringia. Elisabeth is sung by Czech soprano Jarmila Novotná, Hermann by German singer Paul Rehkopf, who was an immensely popular film actor at the time, and German heldentenor Hendrik Appels takes the titular role. The film’s use of Wagner’s opera is done in a traditional fashion, complete with period costuming, traditional frescoed interior palace walls, and the hallmark checkered tile floor. Coincidentally, 1930 marked the beginning of a new era for the Wagnerian celebration that is the Bayreuth Festival. Wagner’s son Siegfried had died and his directorship was taken over by his wife, Winifred, and German conductor Heinz Tietjen. 1930 was also a historical point for the Bayreuth Festival for another reason. Arturo Toscanini, upon the invitation of Winifred, began conducting there. However, his tenure was short-lived, being replaced a year later by German-born Karl Elmendorff. Winifred’s friendship with Adolf Hitler, the association of many members of the Bayreuth Festival of the time with the rising Party, and Toscanini’s outspokenly anti-fascist stance, likely all played a part in his swift replacement.

The other scene sampled by Froelich from “Tannhäuser” is perhaps more famous than the first. This is the “Chorus of the Elderly Pilgrims” in Act Three, part of Tannhäuser’s pilgrimage to Rome to absolve his sins at the behest of Hermann. In the film this is sung by the Berlin Municipal Opera. They were founded in 1925 and serve as the origin of the more contemporary “Deutsche Oper.” Only the final stanza and cathartic “Allelujah” can be heard in the film: “He is not afraid of hell and death; therefore I will praise God all my life!” In the context of the film the choice makes sense. At this point, Bach has been invited to the private apartment of van Lingen and, nervously, she comes to meet him for the first time, not knowing that he is in love with her. In a case of ironic dissonance, the music and the dramaturgy do not align: instead one prefaces the other.

This humorous play of opposites is transformed later in the opera when “The Tales of Hoffman” makes an appearance, serving as both the diegetic music for the film and the opera that the film’s narrative is based upon. During a routine rehearsal of the performance, once can recognize the famous Act Three Venetian serenade between Guilietta and Hoffmann, “Belle nuit, ô nuit d’amour,” sung in the film by Novotná and an unknown mezzo-soprano; possibly an “Irmgard Gross.” The equally famous “Les oiseaux dans la charmille,” or “The Doll Aria,” is also sung by Novotná. Her performance is of the times, with the tempo relatively fast, fast frame-rate and vibrato, and subdued acting, although the rehearsal format is hardly reflective of the final product. Most of the non-diegetic music used in the film was composed by a relatively unknown German film composer, Hansom Milde-Meißner, who was active into the 1950s. But thanks to Offenbach’s “The Tales of Hoffmann” and Wagner’s “Tannhäuser” we get several shining moment in “Fire At The Opera” where a sound film, made at a time of radical redefinition and experimentation in the world of European arts, entangled with the classical, pre-war world of opera.